Shop by Industry

Industries we support...

Products

START SHOPPING...

EXPLORE by category

Product Series

Resources

Contact

Find a Dealer

When shopping for lights, one can be easily overwhelmed with brightness ratings from manufacturers. Companies can advertise impressive numbers for their lights, but then the light may provide mediocre results in the field. It’s good to understand how lights are being measured and if the measurements are consistent across different lights in the market.

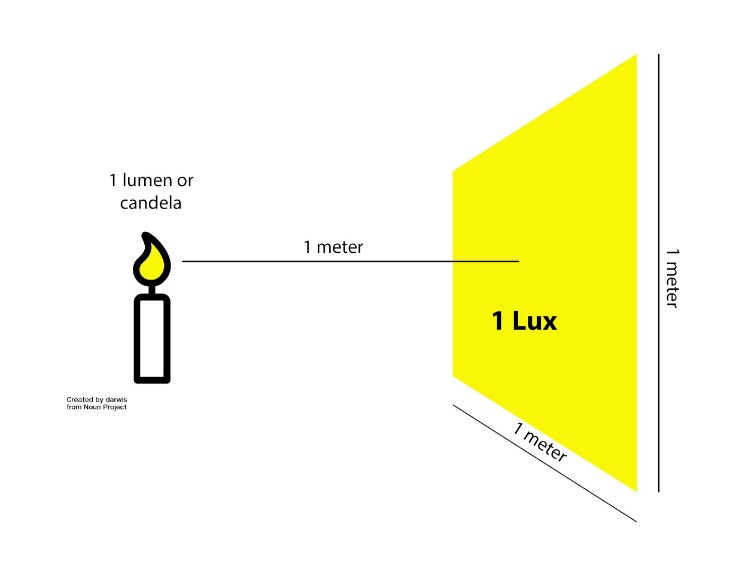

There are many different ways to measure light, but here we will focus on lumen and lux. Before we start, let’s look at where light measurements originated. Before the invention of electricity, the standard of light measurement was a single candle, and the measurement of light emitted from a single candle was 1 candela.

Lumen measures the total amount of light emitted from a light source. Lumen is derived from candela measurements, where 1 lumen equals 1 candela.

Lux measures how much light is illuminating an area at a given distance.

Now let’s look at each of these in more detail.

Merriam-Webster defines lumen as:

A unit of luminous flux equal to the light emitted in a unit solid angle by a uniform point source of one candle intensity

Or, in more simple terms, a lumen is the measurement of the total light emitted from a light source. Now, let’s break this down into two more detailed measurements, emitter lumens, and torch lumens.

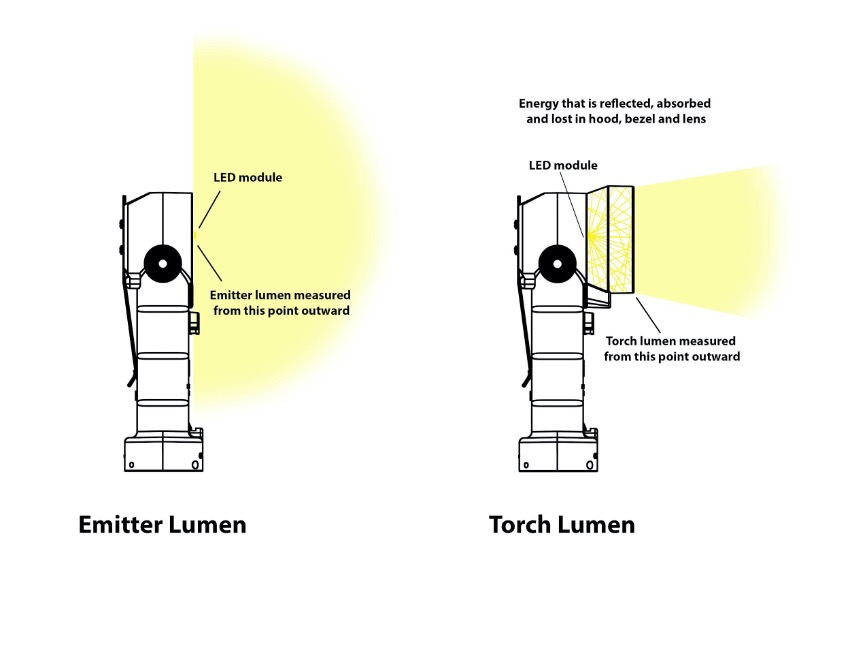

The emitter lumen is the output from the original light source, such as the incandescent filament or the LED module. This is the most accurate lumen measurement because it measures the output from the actual light source with nothing to obstruct, alter, deflect or absorb the energy.

While emitter lumen may be true and accurate in a laboratory, it isn’t as practical for the real world. Most of the lights we use have a housing, reflector, and lens to protect the bulb or LED module and shape the beam for a specific purpose. The measurement of the light output after the reflector, lens, and housing modify it is called the torch lumen.

The torch lumen can be 20-30% lower than the emitter lumen due to heat absorption, lens absorption, and light loss within the housing.

These are Photometric measurements because they are related to human vision (what the eye can see). Instrumentation, such as the photographer’s light meter, allow us to measure light.

What is emitted by a light source may not be visible to individuals. Instruments measure the complete set of energy emitted, and the measurements are called Radiometric, with units in Watts.

Another method of measuring light is lux.

Merriam-Webster defines lux as:

A unit of illumination equal to the direct illumination on a surface that is everywhere one meter from a uniform point source of one candle intensity or equal to one lumen per square meter

Where lumen is the measurement of emitted light as it leaves the light source, lux is the measurement of light as it illuminates a given surface or area. More specifically, lux measures the illumination of a single lumen or candela on a 1 meter by 1 meter surface area that is 1 meter away from the light source.

To give some context to lux measurements, 300-500 lux provides good illumination for an office. The human eye can still read a newspaper without any problems with the lighting of 1 lux.

ArchToolbox provides a good comparison of lux values for different working environments to provide perspective.

Which is a better measurement, and when should each be used?

Light manufacturers often provide lumen data for their lights, and it’s essential to understand what type of lumen information they present.

And lumens are only a measurement of the output of the light, and the lux values should be considered and measured to precisely compare the practical illumination of light.

Cinematographers and photographers use lux because they want to measure the effect of light on a subject and compare the brightness and relationship of the key light vs. a fill light. The best way to do this is with a meter measuring lux.

Lux can also be valuable to first responders to know how much light they need in any given circumstance. If a responder’s work is primarily at 10-50’ away, they will require different and more powerful lights than if they are doing short-range work at an arm’s length.

A small headlamp will provide enough lux for tasks done at arm’s lengths away. A very powerful headlamp or helmet light can cast too much illumination, and this can cause the responder’s eyes to strain and become fatigued over long periods.

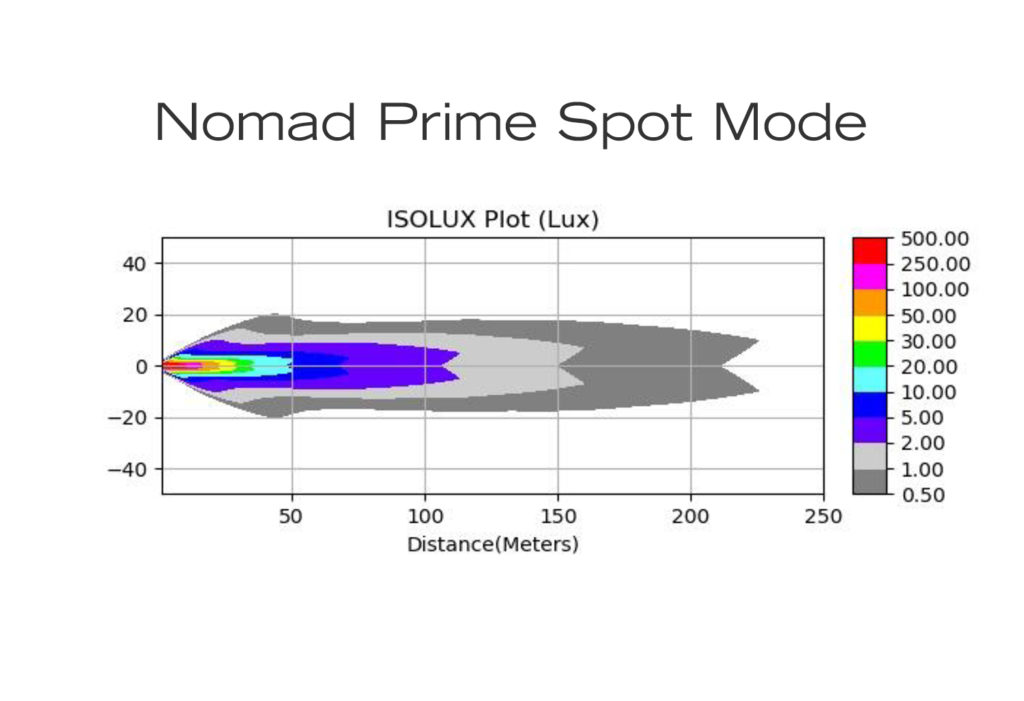

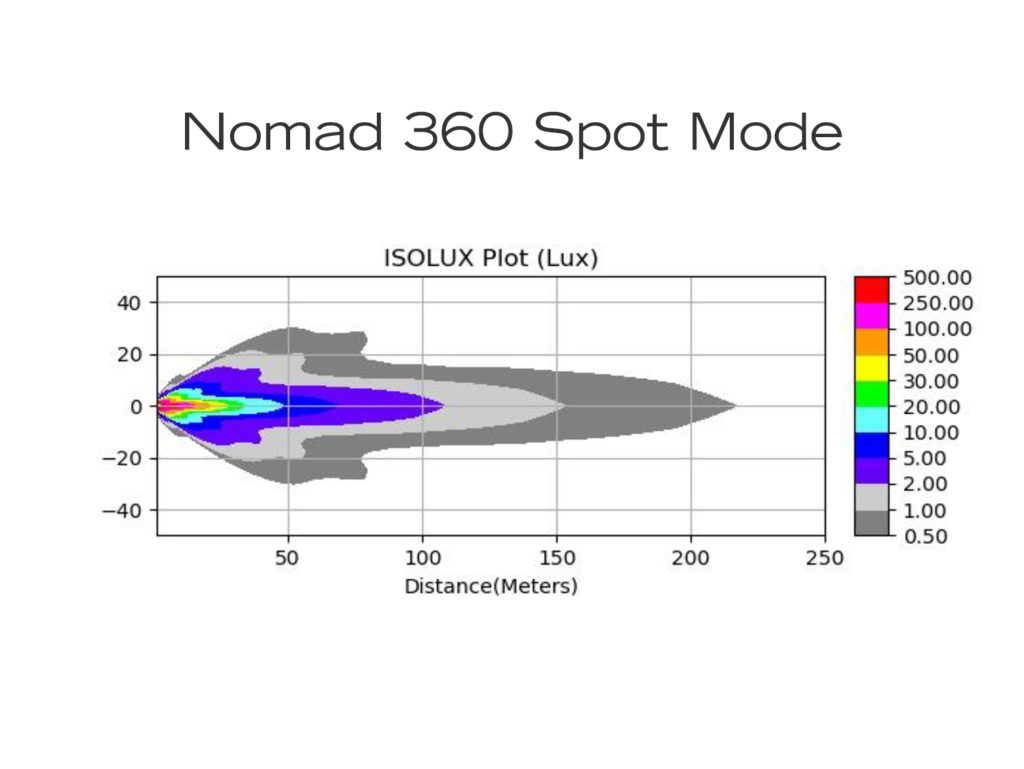

Light distribution refers to the spatial distribution of luminous intensity, and the IsoLux diagrams clearly illustrate the comparison of different light distributions. The most intense illumination is indicated in the IsoLux diagrams by a red color. As the distance from the light source increases, the illumination intensity also decreases and changes accordingly from yellow to blue to gray.

Here are examples of ISOLUX data on the Nomad Prime in Spot mode and the Nomad 360 in spot mode.

The Nomad Prime is a high-powered portable spotlight. Here, you can see that it has a relatively narrow beam that stretches out to almost 250 meters (750 ft). If one can comfortably read with 1 lux, you would have enough light to read at 150 meters (450 ft).

The Nomad 360 in Spot mode provides a wide beam of workable light in the short-range but still casts a long, narrow beam over 200 meters away.

Understanding how to measure light and different methods helps determine what type of light you need. Measuring the number of lumens that a light emits doesn’t always tell the whole story. The type of LED, reflector shape, and lens can all affect the quantity and quality of that light.

Considering the lux and lumen measurements and the light design will give you a complete picture of how much illumination a light provides.

Enter your details below to save your shopping cart for later.